About

Keith Terry is a percussionist/rhythm-dancer/educator whose artistic vision has straddled the line between music and dance for more than four decades. As a soloist he has appeared in such settings as Lincoln Center, Bumbershoot, NPR’s All Things Considered, PRI's The World, the Vienna International Dance Festival, and the Paradiso van Slag World ...

Contact

Loops of Experience: How Long Creative Cycles are Key to Cross-Cultural Creation

Body Musician Keith Terry will be the first to tell you: Collaborations across cultures can’t happen in a week or month, without feeling like a mere play of surfaces, like something slapdash, and hoc. They demand time. It takes years, decades for collaborators to find their way through the thicket of cultural details, to make new meaning together. Elder artists have the distinct advantage, especially those who keep returning to that touchstone of imagination, who keep building relationships. Who circle back in long creative cycles.

Extended cycles have defined Terry’s diverse, looping engagement with how movement, music, and rhythm entwine across cultures. His own career has circled back repeatedly, always with fresh perspective and deeper understanding, in ever-richer collaboration and dialog with artists from elsewhere.

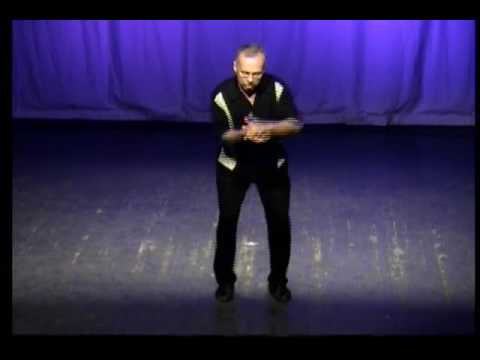

From his start in jazz drumming and later in tap, Texas-born, Bay Area-based Terry has embraced the rhythms of Bali, Brazil, West Africa, and southern Europe, bringing together a growing community of like-minded artists from across the globe who dance music and make gesture sonic. He’s created his own style, Body Music, which he has taught, performed at major festivals and venues around the globe, and refined over decades, most frequently as a solo performer. His achievements won him a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2008, the first time an artist of his kind was chosen as a fellow.

Yet it is Terry’s profound and long-lasting collaborative, cross-cultural efforts with co-creators from Bali to Brazil, the great loops in his art that point to his uniqueness as an artist. Terry first heard the gamelan at a rehearsal in Berkeley, CA. He was transported. The gongs, punctuating long unfurling rhythmic cycles, had a powerful physical presence he had never felt when simply listening to the music on LP. “The big gongs move air, in a way you can’t capture on a recording,” he recalls. “It was a total body experience.”

That first live experience of gamelan has repeated, amplified, for forty years. The music led Terry to kecak, a rhythmic chant and movement-based form that evolved in Bali’s village communities. He connected with I Wayan Dibia, a revered practitioner of kecak who created large-scale pieces for the stage based on the tradition. “It was a natural combination for both of us. The rhythms were compatible, as well as the movement. Kecak is performed in concentric circles, sometimes standing, mostly sitting. There are lots of hand and finger gestures, lots of choreography and synchronized group movement, even though kecak doesn’t move in space. I was drawn to that, how dynamic kecak is, both sonically and visually. I saw it as a part of Body Music.”

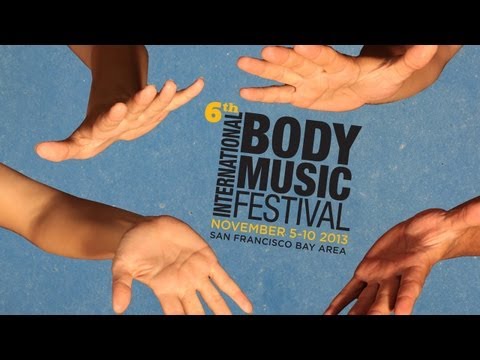

Flash forward forty years. After decades of work with Indonesian artists, Terry organized an edition of the International Body Music Festival—a moveable feast celebrating humanity’s oldest instrument that Terry founded in 2008. He and his long-time collaborator and friend I Wayan Dibia were putting together a huge ensemble to perform a variation on a traditional Balinese dance/music form called kecak.

In one village, Terry was asked to teach a few short phrases of movement to the assembled performers. He did so, but nothing seemed to click with the group. Then Terry let go, setting aside explicit instruction and considering how the village performers might best relate to the material. He focused on his intention, on the phrase itself. The performers began to synch up.

As they did, something extraordinary occurred. “I don’t know exactly what happened, but it was like lightning bolts, fire, sparks. Everyone was smiling, and many later told me they experienced the same thing,” reflects Terry. “The kecak locked, and it moved me. I felt deeply how connected I was to these people in this moment. “The intensity was like nothing before. The cycle had ended, booming like a gong.

It took decades to bring the work to fruition. “In effect, we worked for ten years, from 1980 to 1990, before we brought all the pieces and elements together. And that set of projects defined the scale of a great deal of my future work: I started doing big international collaborations in Bali and began bringing international artists to the States from Bali,” recounts Terry, sometimes uniting as many as a 100 performers. “Having the International Body Music Festival in Bali in this year brought this huge loop back around. This summer, when we had nearly a hundred performers from outside of Bali come to work together, I knew that this is a long cycle that has completed, a 35-year cycle.”

There are other cycles at play for an artist with decades of work behind him. Terry comes to collaborations with a different spirit now, happy to share his knowledge but striving to make space for new, unexpected voices. “I keep reminding myself that it’s natural for a younger artist to strive to take over,” Terry notes. “I want to encourage that because that’s how it works. But it’s also hard for me to let go. It’s a constant reminder I have to give myself. At some point, you need to step back and let things unfold.”

When your creative medium is your body, age affects you. Terry has traded youth’s flashy athleticism for effortless expressiveness—though he remains a remarkably dynamic performer and continues to tour. (He will be bringing his work with Body Musicians from Spain, France, Cuba, Greece, and the US to the 2016 IBMF in Paris, before coming to the States in 2017.)

“I feel my age at times. But I’ve been blessed with energy and I am a high-energy person. I’m not as athletic as I was, but there’s a distilling of the essence of the music, of the movement. I do less, but I have far more momentum, more behind what I do. I am in the tracks of the cart on the muddy road that was laid down over decades, if not centuries. I feel like I’m in those tracks now, enjoying them. I feel what came before.”